During the quiet months of winter, the ponds at Schlitz Audubon are still. Often frozen over, pond life in winter seems to disappear. You might ask where the pond creatures are. The answer provides a unique lesson in adaptation.

Ponds at the Center are home to both reptiles and amphibians, and they need to make incredible changes to survive cold weather and freezing habitat. We see reptiles and amphibians at Mystery Lake, Teal Pond, and Turtle Pond, among other ponds on the Center property.

Reptiles and Amphibians in our Ponds

Reptiles are air-breathing, cold-blooded vertebrates with special skin comprised of scales or bony plates. They breathe through their lungs and lay soft-shelled eggs. Turtles are reptiles, and at the Center, there are painted turtles, snapping turtles, and Blanding’s turtles.

Amphibians are also cold-blooded vertebrates that breathe through lungs, but begin their life in a larval stage as tadpoles with gills. Amphibians in our ponds include frogs, toads, and salamanders.

All of the main ponds will host frogs such as American bullfrogs and green frogs. Spring peepers and gray tree frogs inhabit Turtle Pond and Teal Pond. All have breeding populations, and while the wood frog has been observed, we haven’t found an established breeding population.

The Great Adaptations in Winter

An amazing transformation takes place in winter. Aquatic reptiles and amphibians enter a state known as brumation, similar in concept to hibernation, but markedly different. Brumation is triggered by shorter day length and temperature changes. Aquatic pond creatures’ metabolism slows down to such a point they don’t need food or too much water. Before entering brumation, the animals eat a lot of food so they then live off of nutrients they have stored in their bodies, including fat and glycogen. It is not a true deep sleep like hibernation; pond animals will wake up and swim around.

Wood frogs survive the winter uniquely. When it gets cold, they will move to a crack in a log or dig into leaf litter for their winter abode, and they will freeze! Their tissues freeze, except for their internal organs, which slow down—a lot. Wood frogs remain frozen until the warmer temperatures of spring cause them to thaw out, after which their heart will beat, and they will crawl onto the surface again.

Wood frogs are the most freeze-tolerant of the frogs, so their range extends north into the arctic. Most northern tree frog species, like the gray tree frog and spring peeper, are also freeze-tolerant, but not as much as the wood frog.

Blue-spotted salamanders, which are a type of mole salamander, are not freeze-tolerant. They avoid freezing by digging underground deep enough to avoid the frost and spend the winter there, up to 50 meters from their home pond. During winter, aquatic frogs, like bullfrogs and green frogs live under water at the muddy bottom of the pond, where they change color to become brown like their surroundings. They don’t borrow into the muck like turtles do.

Breathing Underwater

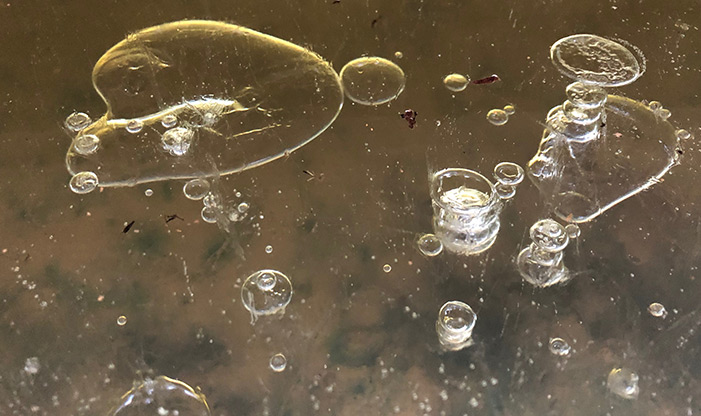

Brumating reptiles and amphibians still need to breathe despite being dormant. Frogs have lungs, not gills. When they’re underwater, they breathe through their very thin, porous skin. Frogs absorb oxygen from the surrounding water. Oxygen is more highly concentrated in water when it’s cold, so frogs can only breathe underwater in winter and early spring. In the warmer months, frogs breathe above water through their lungs.

Frogs need to have a skin response to breathe like this. It‘s the reason they don’t burrow. Turtles have some thin skin through which to breathe, but they mainly breathe through a process called cloacal respiration. Essentially, this means they breathe through their butt. Because of this, they can burrow beneath the muck on the pond’s floor.

If you’re lucky, you might see a frog stir about on the bottom of the pond, even in the cold. They slowly move in and out of brumation throughout the winter. When the temperature fluctuates, reptiles and amphibians will wake up, so you might see them stir beneath the ice or come up to sun themselves. This season, visitors have reported seeing salamanders due to unseasonably warm temperatures on the trails at the Center.

Even though pond life is not as visible in winter as it is during warm months, it is still there, but hidden. If you happen to hike by Mystery Lake, look beneath the surface of the ice, especially on a milder day. You never know, but you might see a frog waking up to take in some sunlight.

Updated to reflect pond name changes.