Spring at the Center is a time to witness rebirth. We witness blossoming ephemeral wildflowers and ponds teeming with Fairy Shrimp and other aquatic species, all while a variety of birds announce their return overhead.

When we notice these occurrences and record our observations, we’re engaging in phenology. Phenology is the study of when things happen, in particular, the study of natural phenomena. Belgian botanist Charles Morren first used the term in 1849 to describe, “the science having the goal to understand the manifestations of life governed by time.” In Wisconsin, we have the richly documented phenological heritage of Aldo Leopold, who recorded the seasonal cycles at his shack along the Wisconsin River.

The Workings of the Phenologist

We can view phenology as being an active observer of one’s surroundings. The phenologist stops to not only smell the Wild Plum or Chokecherry – but may also note how powerful the scent, or where the plants are in the growth cycle. The phenological mindset is a more nuanced approach to enjoying the flower and understanding it. Observation is a key step in the scientific process. Observation leads to the question: Why?

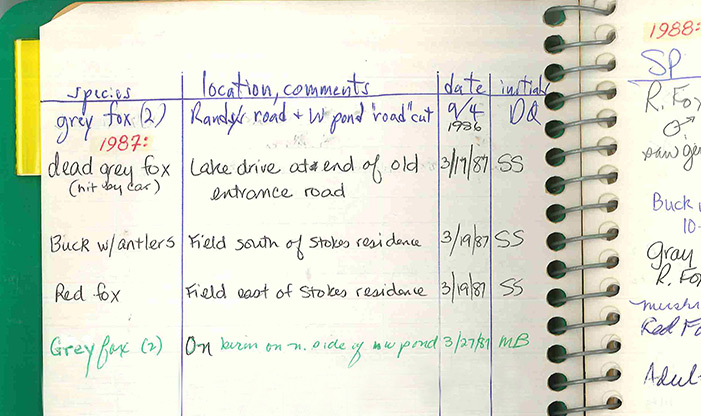

Chances are good you’ve been undertaking the first steps to phenology your entire life. You might notice when cardinals become your alarm clocks, when you see your first Monarch Butterfly, or when trees begin to bud. Noticing when things first happen or stop happening in the year are all steps toward phenology. The next step is to record the dates of these events to compare against the data of other years.

Arrivals and Disappearances

We often first understand phenology to be the seasonal times at which plants appear and animals arrive. But the keen observer gradually begins to notice the disappearances as well. These can be seasonal disappearances, such as when the forest becomes considerably quieter after spring birds migrate farther north. But they can also be gradual long-term trends. Tracking the timing of these events creates valuable data that provide clues regarding the health of habitats and ecosystems. The disappearance of plants and animals, whether seasonal or historical, provides a windfall of information—if we’re willing to pay attention.

Phenology at the Center

The most visible example of the practice of phenology at Schlitz Audubon is our Bird Chart in the Great Hall, a phenological study started in 1974 by our dedicated birders. Birders mark how many of each species they see on a given day, providing a historical record of arrivals and departures. This information is then entered into eBird, a world-wide, online database managed by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology .

By comparing contemporary records to those of the past, these records illuminate trends of the present, and help predict conditions of the future. We record disappearances in negative space, when looking at data and realizing what is no longer happening, and when. That can lead us to hypothesizing the “why,” and how we can best work to support species with our habitat creation efforts.

One perfect example of the cascade of phenological observation is the cycle of Skunk Cabbage, one of the first plants to blossom in springtime. Skunk Cabbage is pollinated by small fungus gnats, which are also eaten by birds. Each is interdependent on the other. If synchronization goes awry between the gnats, Skunk Cabbage, or birds, this will become apparent in the responses of the populations of the complementary species. Our Nature Preschoolers love celebrating when they begin seeing Skunk Cabbage blossoming on the trails, a sign that spring has arrived.

Using Phenological Observations

Land managers also use certain species of plants as a litmus to orient within the seasonal growth cycle. In this region, we use the blooming cycle of honeysuckle and the height of Kentucky Bluegrass as growth indicators. At the Center, we have a plot of Kentucky Bluegrass and keep track of its height. From these observations, one can then make hypotheses regarding how to best care for the land and its unique and interconnected habitats.

On our Nippissing Great Lakes Terrace, we have infestations of invasive Dame’s Rocket and Garlic Mustard. Our goal is to mow down invasives at such a time they will not have dropped seeds, nor will be able to subsequently flower. We need to pay close attention to the phenological stages of these plants, which indicate a perfect timing window of about two–three weeks every year to execute our mowing operations. Missing this brief window just once could set all of our progress back by years.

Being on Lake Michigan, we have the longest and latest growing season in the state. Our seasonal phenomena takes place on a different schedule than natural areas just a few miles west. Moisture, rainfall, soil type, temperature—each of these factors and more affect the growth cycle. Going by a date on the calendar is not sufficient—nature has its own schedule. Phenology is one way to measure how climate changes over time. We can then seek the reasons behind the changes.

The Observations of a Phenologist

The Center’s former Senior Ecologist Don Quintenz, who worked here for over 30 years, recalls his mother writing her seasonal observations on their family calendar on a daily basis. This can be a great way to share the seasons with your family and teaches children situational and seasonal awareness.

Years ago, Don observed that he always began to hear Sandhill Cranes in the third week of March. Aldo Leopold wrote, “the crane is wildness incarnate.” In Wisconsin, Sandhill Cranes are beacons of spring, as their overhead rattle call echoes off the surface of our thawing bodies of water. These birds nearly became extinct in our state; by 1940 Wisconsin had fewer than 1,000 Sandhill Cranes. The phenologists noticed their absence. When will you hear the call of spring?

Written by Ed Makowski with Contributions from Michelle Allison, Don Quintenz, and Marc White